EN

Carlos Tê © Guilherme Costa Oliveira

His name is Carlos Monteiro, but everyone knows him as Carlos Tê. Tê for "tarado musical" that means “musical freak”. The nickname comes from his teenage years and attests to his melodic vein. He is the author of song lyrics that we all know by heart, but which he himself says he can't remember. “I have trouble memorizing. Even the songs I love most by others, I don't know them by heart; I know the melodies,” he confesses.

As well as being a lyricist, he has published different literary genres - poetry, short stories, novels and theater. His latest book, A Invenção do Canto e Outros Versos (The Invention of Singing and Other Verses), from the “Poema Letra” series in the Plural collection by Imprensa Nacional - Casa da Moeda, brings together lyrics of his that have become “song classics”, such as “Porto Covo”, “Jura”, “Porto Sentido” or “Chico Fininho”, by Rui Veloso, but also “Problema de Expressão”, by Clã, or “Primeiro Beijo”, by Cabeças no Ar, among many others.

We met at the Porto Book Fair, where he was a guest in the cycle “É Urgente o Amor”, for a chat about lyrics and poems, but also about music, a central element in his life. And we started precisely with music. Today, Carlos Tê complains about the “lack of silence” and the abusive use of music as a way of filling silences. “Music is no longer mysterious, it's always on offer,” he says.

Our relationship with music has changed. Music has come to be heard differently. It doesn't mean we listen to it more or less. The importance is different. Our attention is being fought over by many more things. On the one hand, that's good, it's a sign that there are more things happening, but I grew up with the idea that all things come from there; everything that is mysterious, everything that is apotheotic, everything that is encrypted, is there in the voice,” he says.

In this sense, Carlos Tê regrets that music has “lost its centrality” in people's lives and in music festivals themselves. In this regard, he shares his experience at Porto Primavera Sound in 2016: “I went to see PJ Harvey, an artist I love; I arrived a little late, looked ahead and saw three thousand people who are already experienced - I wasn't experienced - all huddled around the stage because they already knew..., but I stayed behind. And nobody was listening. Everyone was moving around, everyone was drinking beer, and every time I changed seats at the concert, I got people talking. Those who really wanted to listen were at the front.” And he continues: “Even more perverse is the fact that there are more stages [with simultaneous concerts] and even a concert like that, with a ‘great sound’, with a beautiful light show, always with the effect of going dark and silent, was totally sabotaged by the noise and lights coming from another stage. I thought: F*ck, this is absolute conspiracy! Music is dead! - I mean, music exists, but not with the solemnity it used to have. I realized I was at [music's] wake.”

At a time when music is consumed mainly through streaming platforms, Carlos Tê evokes the vinyl era: “You listened to a record in an almost reverential way,” he says, adding that he used to get his friends together to listen to it. “Everyone had their own intimate relationship with a particular song - that's not to say it doesn't continue, but now it's different; bouncy, hyperactive, and it also has to do with what technology has given us.”

Carlos Tê © Guilherme Costa Oliveira

A Invenção do Canto e Outros Versos © Rui Meireles

The invention of song

When he was 15, he wrote his first song in English (it was called “oh life, don't die”, he says laughing). Because he grew up in a dictatorship, he came to have an “aversion” to the Portuguese language. “I felt I was trapped in this language,” he says. That's why, for Carlos Tê, “living and thinking in another language was liberating”. He was 18 when the "Carnation Revolution" happened and “there was a process of reconciliation” with the Portuguese language. But he always felt more connected to Anglo-Saxon music (“pop music was a kind of wicket over the outside world”), although he admits that he “often didn't even pay much attention to the lyrics”. “I grew up listening to the songs and completely ignoring the lyrics. I didn't give a damn, because I only listened to the voices,” he says. That's why, in the preface to his book A Invenção do Canto e Outros Versos, he refers to the importance of the voice.

“Voices are what bring us closer to things or not.” According to him, the voice is “the arrow of the song”. For the lyricist, the words “are intrinsically strong”, but it's the voice that throws them into a dimension that he himself, who wrote them, “wasn't expecting”. “That's a mystery that I've been struggling with and that continues to fascinate me over time,” he stresses.

Although he considers that “the voice is everything in a song”, he admits that when he writes lyrics he never thinks about who will sing them and, perhaps for this reason, he doesn't usually write to order. “It can happen, but it's rare.” According to Carlos, songs “have some kind of need to appear”. “You never know what it's going to be; if it's going to be a good song, if it's going to be weak, if it's going to be fast, if it's going to be slow, I don't know, I have no idea. Because it's a growing process. It could even be nothing. Most of the time, it comes to nothing,” he laughs.

The discovery of poetry

He was born in Porto in 1955 and at the age of 14 he had his first job in an office in the automobile industry. At the age of 24 he went on to study philosophy, but would rather have majored in history. He tells us that he “always had a passion for words, especially their sound”. “There's an acoustics to words... And there are beautifulPortuguese words, and then it becomes a bit of a game, a playful thing, you start to connect things...”

The author shares with us the discovery of “a very important text” whose reading changed his perspective on writing and poetry. “It was a song I didn't like very much, but the poem was fabulous, 'Lágrima de Preta', by António Gedeão [published in 1961]; it's a poem by a chemist and there it is, dismantling racism; this was in 1970, and that was pure poetry for me. And it met my unknowns, my questions. For me, poetry became that,” he says. And he adds: “But it was also the illiterate poetry of António Aleixo, that popular poetry that dismantles the rich. I thought: these people know too; they can't write, but they know. There's poetry here too. I began to realize that poetry could be anywhere. And when I heard the work of José Mário Branco and Sérgio Godinho, who were at a much higher level, I thought that's where I wanted to go. And then it happened with April 25th, with all the doors open...”

Are they lyrics or are they poems?

Although he considers that the process of writing lyrics and poems “is similar”, and that “sometimes a poem and a song start with the same phrase”, Carlos Tê makes a distinction between the two: “writing a poem is a long journey, which requires maturing, it can take months; and a song is an almost vertiginous journey, very fast. The similarity between them will sometimes be a phrase that sparks something, that launches something.” The lyricist also maintains that while the lyrics of the song “only gain strength when they are sung”, in the poem there is “a magnificent solitude”.

But, after all, can't lyrics and poems be the same? Can't a poem become a song and a lyric become poetry? Carlos Tê admits yes. “When can a song be a poem? I understand that texts take on a kind of life, they communicate with the creator and command the creator. The creator just has to know how to listen and be attentive. I feel that there are things that want to go in a certain direction... Sometimes they start off going one way and then go another, and you have to have the humility to realize that it has a will of its own, and you have to establish some kind of pact,” he says.

Carlos Tê © Guilherme Costa Oliveira

“I'm a bit fascinated by characters with no history.”

Álbum Ar de Rock, 1980 © Fonoteca Municipal do Porto

The lyrics of his songs are full of characters - from “Chico Fininho” to the “Rapariguinha do shopping" (little girl from the mall”) to "Guida peituda" (“busty Guida”). None of them, he says, are real. “Real stories for me are never literal. There's something from reality that serves as a starting point, but then I imagine it. I cheat all the time,” he laughs. “I start adding things; it's pure cheating in typical writing. There isn't that literalness of having to respect that lady's story,” he says. “Chico Fininho himself doesn't exist, but there were people who convinced themselves that he did, who came to tell me that they knew who he was.”

A song about gel nail extensions

Carlos Tê admits that he is “an impressionist” who is interested in ordinary people he meets in everyday life. “I'm a bit fascinated by characters with no history, no historical dignity. 'Why write about Chico Fininho, a bastard?' Why not? I'm a bit fascinated by that kind of character. Literature gives dignity to what apparently has none,” he says. In this sense, he adds that “one of the last things he really enjoyed writing is the lyrics to a song about gel nails”.

“I never thought it would be possible to write a song about gel nails, but once I was at supermarket and I saw a very pretty girl at the checkout, and she had gel nails and was hitting the keys with absolutely brutal skill. So I thought about the life of that woman, who probably had a child she changed diapers for, and peeled potatoes, like I do, and so on,” he says, amused. He adds: “I didn't rest until I'd written a song about that kind of suburban character. And I think it's possible to have poetry in there. Poetry is whatever you want it to be. That's what often moves me. Happy people don't have much interest. It's a bit like that thing where happy people don't make great characters.”

There are many song lyrics whose subject is Porto city. In fact, many of them accompany the city's history, such as “a rapariguinha do shopping”, which depicts the opening of the city's first shopping center. “It's the transition from the small fabrics store to the store at the top of the escalator, which has status, it's something different,” she jokes.

O Comboio do Interior (The Inland Train)

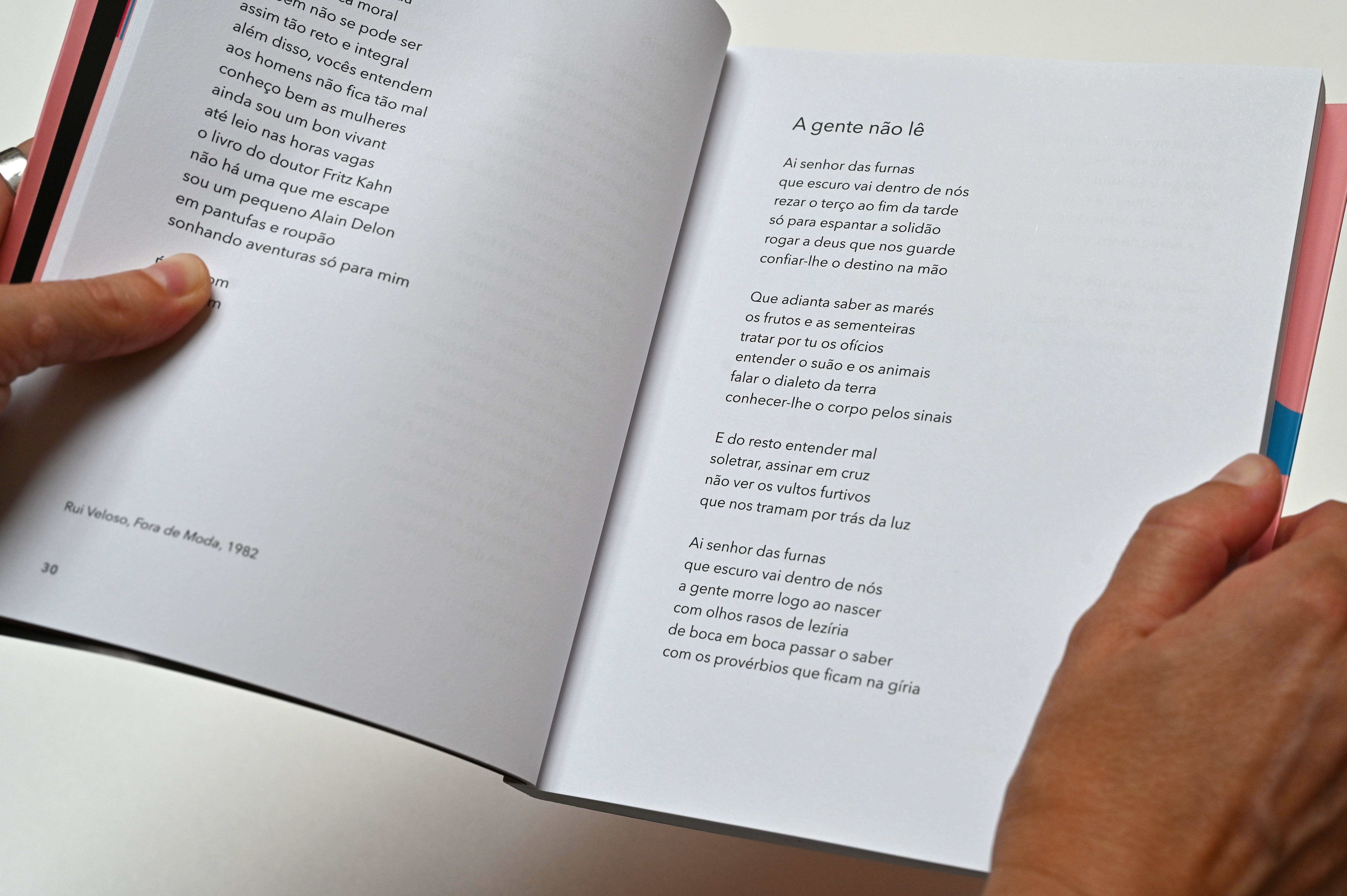

At 69, he continues to write songs and says that “his great driving force is curiosity”. He is currently working on a project that he wants to turn into an album: O Comboio do Interior. “It's a set of songs that tell several stories; almost every lyric has a reference to a disused line, a station... A train driver travels to the countryside and meets people,” he reveals. The author tells us that this project has to do with “the fascination” with his paternal roots, “which are illiterate grandparents from the Douro and 'deep' Trás-os-Montes”. “It's the continuation of the song 'A Gente Não Lê', which I wrote in '82; that was the starting point,” he adds.

“Even today, that's one of the lyrics people talk to me about the most. It's amazing how, 40 years later, people still come up to me to talk about that lyric,” he says, and reveals that he wrote it when his grandmother died. “It was a farewell song to someone I didn't appreciate much in life, but from whom I inherited a lot.”

He confesses that he doesn't like looking back at the past because, he says, “the great danger of the creator is self-contemplation; looking back is the beginning of the end”. Even so, we asked him if there aren't any lyrics that he is still proud of today, considering that they are part of the Portuguese collective imagination. He mentions “A Gente não lê”, “Problema de expressão” and “Porto Sentido”. “There are some strange lyrics that say this or that to people, and sometimes I don't understand why,” he says, amused.

"A gente não lê" em A Invenção do Canto e Outros Versos

However, he insists that the voice is the most important thing. “Lyrics don't have to be about philosophy. The songs I like the most, [I don't like them] because of the lyrics; the lyrics aren't the most important thing,” he says. “For me, it's still the voice; the way that voice travels through space and comes to me. It's phenomena like Amy Winehouse, for example. I don't care what Amy Winehouse is singing about; I don't care if it's the phone book or the grocery list. I don't care. What I do care about is that that voice touches me. If I can put amazing lyrics to it, then we're adding up. Fantastic. But for me, that's not the main thing,” he says.

In Portugal, he points to Salvador Sobral as “one of those phenomena”. “He's perhaps the greatest singer of his generation, and the proof is that he won a festival that was impossible to win without people understanding what he was singing. His voice was full of something that touched Finns, Latvians... who didn't know what he was singing. It's that mystery. It's an almost religious mystery. There's no turning back from a great voice. And when I say great, it's not a voice that does the pin; it's not that voice that does 30 in a row, that goes up and down. No, it has nothing to do with that. Sometimes it's three notes. And with those three notes you wonder: what is this?”

By Gina Macedo

Share

FB

X

WA

LINK

Relacionados